SPONSORED CONTENT

Increasing the default pension contribution rate would boost many people’s income in retirement. But the longer this change is delayed, the less it will benefit today’s workers.

The UK is under-saving for retirement. The current minimum auto-enrolment contribution rate of 8% is not enough to meet many people’s future retirement income needs.

Half of defined contribution pension savers are not on track for the income they expect, indicates modelling by our think tank, Phoenix Insights. This equates to around 14 million people.

The questions for policymakers, then, are what can be done to address this problem – and when?

First, band earnings for auto-enrolment should be removed, and the participation age lowered to 18. Second, contribution rates should then be increased from 8% to 12% over time.

Of course, any government would need to avoid increasing contribution rates when households and businesses face particular financial challenges. (See Auto-enrolment: how and when should default contribution rates rise to 12%?.)

At the same time, delaying this increase could also be costly, finds new research by Phoenix Group, our parent company.

Produced in partnership with WPI Economics, the research explores the costs of delay. It highlights the potential strain on social support systems and increased poverty among retirees if policy change is not introduced.

(For more details, see the report, Falling behind the curve: The costs of delaying an increase in auto-enrolment contributions.)

The costs of delay

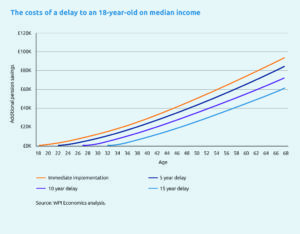

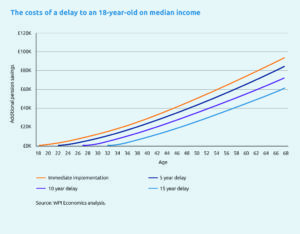

Let’s start with an average 18-year-old today. The research finds that increasing default contributions immediately would probably lead to them having around an extra £96,000 in their pension at retirement, or £64 more per week (see Figure 1).

If the policy change was delayed by 15 years, they would have an extra £61,000.

Figure 1: Delaying the increase in default contribution rates could cost the average 18-year-old £35,000 in retirement

Savings gap

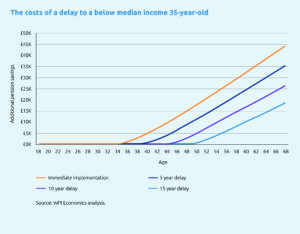

Delaying the increase in contribution rates to 12% would make less of an absolute difference to older people. But the difference is still important.

Take, for example, a 35-year-old on 80% of median income. If this increase was made immediately, they would have an extra £44,000 in their pension at retirement, or £29 more per week (see Figure 2).

If the policy change was delayed by 15 years, they would only have an extra £18,000 in their pension at retirement.

In other words, this saver would lose more than half the benefit (£26,000) of the increase in contributions as a result of a 15-year delay.

People aged 35–44 are confident about saving enough for retirement. But they typically have a saving gap of over £100,000, indicates Phoenix Insights’ Longer Lives Index. This suggests a huge disconnect between their perception and reality.

The use of default rates might therefore be an important way of boosting saving levels among this group.

Figure 2: Delaying the increase in default contribution rates could cost many 35-year-olds around £26,000 in retirement

Window of opportunity

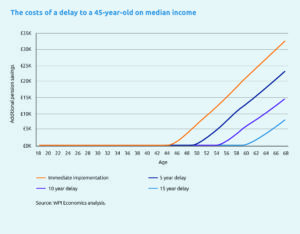

And what about a typical 45-year-old? Many people of this age are concerned about how to fund their retirement.

On average, they only have £88,000 in retirement savings, and six-in-ten are trying to save more for retirement, estimates research by Phoenix Insights.

Increasing default contributions to 12% could lead to them having an extra £33,000 in their pension at retirement, or £24 more per week (see Figure 3).

However, the window to support this group’s retirement incomes by increasing default contributions is closing.

For example, if the policy change was delayed by 15 years, they would only have an extra £8,000 in their pension at retirement.

Figure 3: The window to support a 45-year-old’s retirement income by increasing default contributions is closing

Next steps

The next Parliament represents a critical opportunity to improve savings levels and support workers’ future living standards in retirement.

But system change is needed. So we recommend that legislation is put in place for a new Statutory Requirement to review long-term pensions adequacy.

This would be followed by an annual assessment against economic indicators, to understand whether the timing is right to increase default contributions.

The initial review should consider:

- How we manage the short-term costs to households and businesses, as explored in the report, Raising the bar: A framework for increasing auto enrolment contributions.

- The costs of delaying action – for savers, the national economy, and the benefits system – as explored here and in the report, Falling behind the curve: The costs of delaying an increase in auto-enrolment contributions.

- How this interacts with wider provisions, in particular the role of the State Pension and Pension Credit.

As part of this analysis, it is important that government engages with employers, unions, personal finance charities and other groups with an interest in pension contributions.

The findings of this annual review should be communicated widely, and promoted through an annual campaign.

This will help to ensure that future governments are held to account for increasing auto-enrolment contributions.

Without such action, many workers’ retirement income expectations will not be met.

The post Gail Izat: Auto-enrolment – why not increasing contribution rates to 12% could prove costly appeared first on Corporate Adviser.